Ovenbird © Tom Murray

The Ovenbird, whose familiar tea-cher, tea-cher, tea-cher, tea-cher song is a dominant feature of the spring and summer woodlands of New England, was identified in Breeding Bird Atlas 2 as a species on the increase, especially in the central and eastern portions of the state. These increases were thought to reflect increased amounts of suitable forest habitat due to formerly agricultural land reverting to forest.

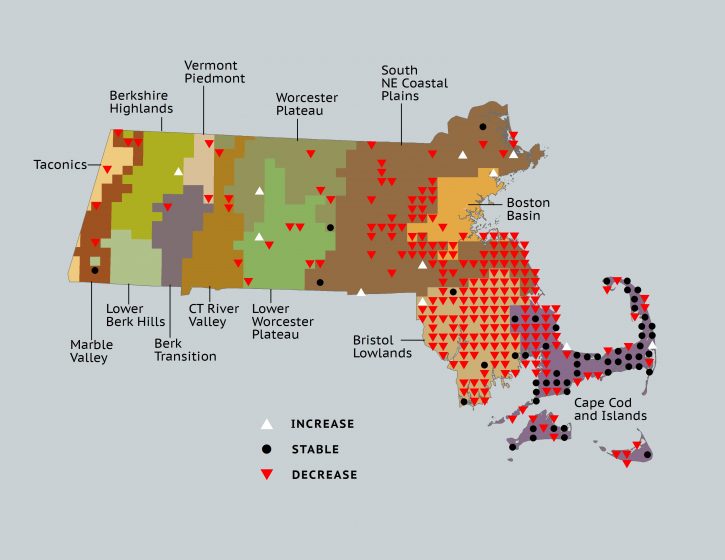

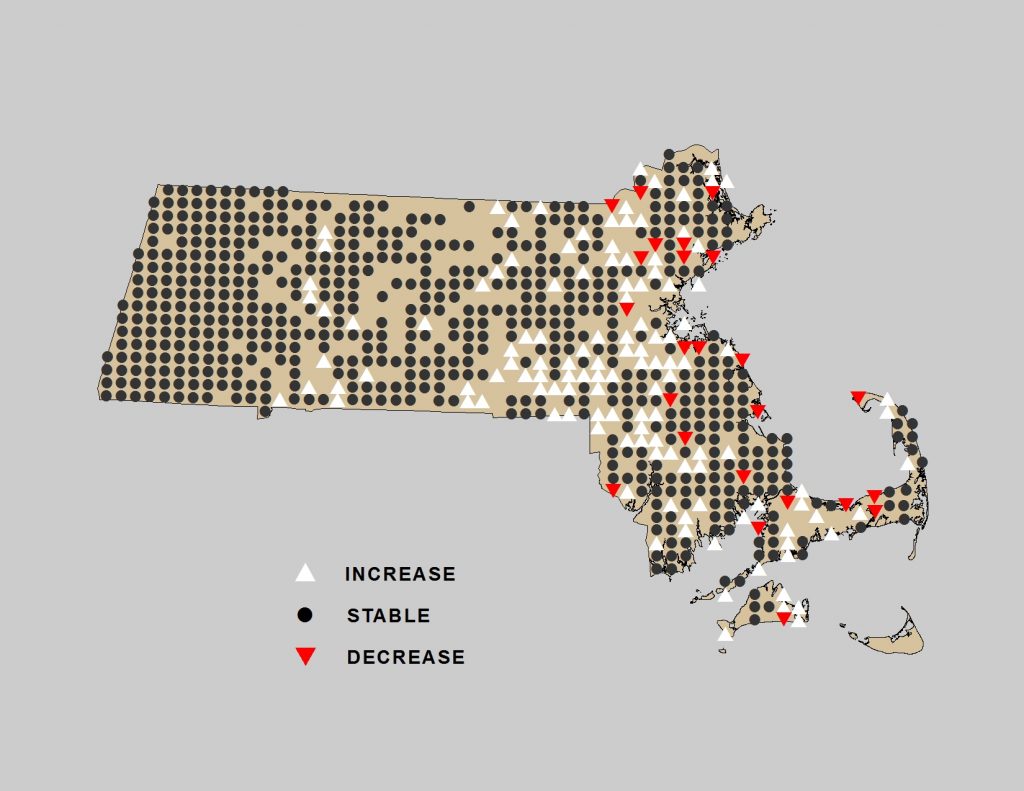

Change in Ovenbird distribution in Massachusetts between Breeding Bird Atlas 1 (1974-1979) and Breeding Bird Atlas 2 (2007-2011).

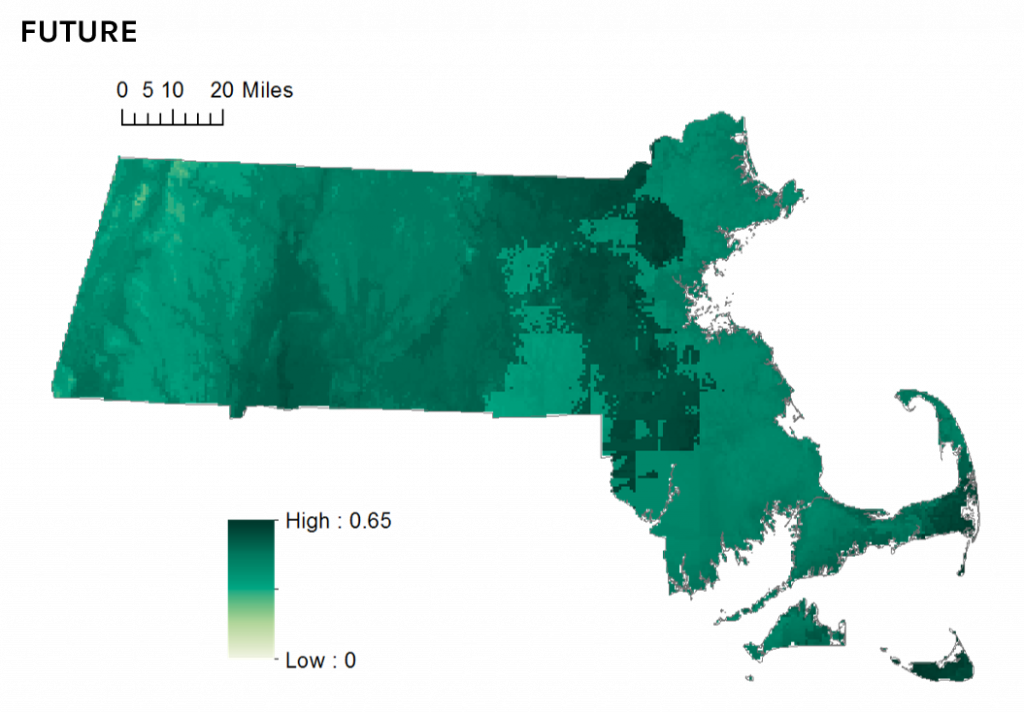

But the newly-released State of the Birds report tells a less optimistic story. Ovenbird distribution in Massachusetts is likely to be adversely impacted by projected future changes in temperature and precipitation patterns. By 2050 the species will continue to occur statewide, but occupancy in eastern areas of the state may decline as the species’ climate envelope (their preferred climate) drifts northward, leaving Massachusetts near the southern limit of the species’ continental distribution.

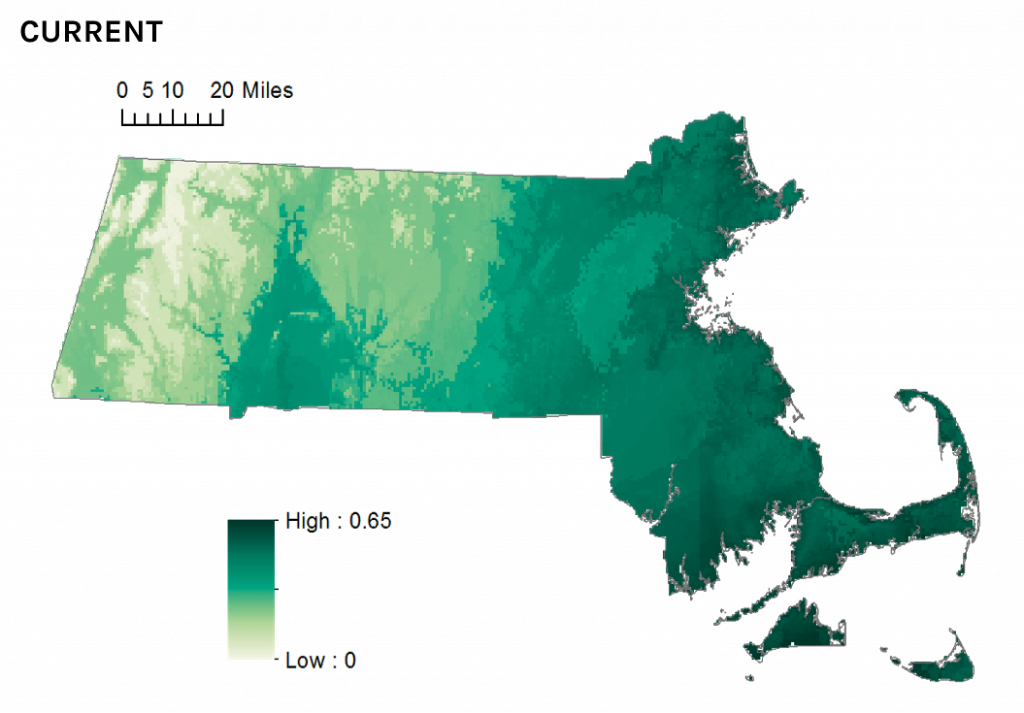

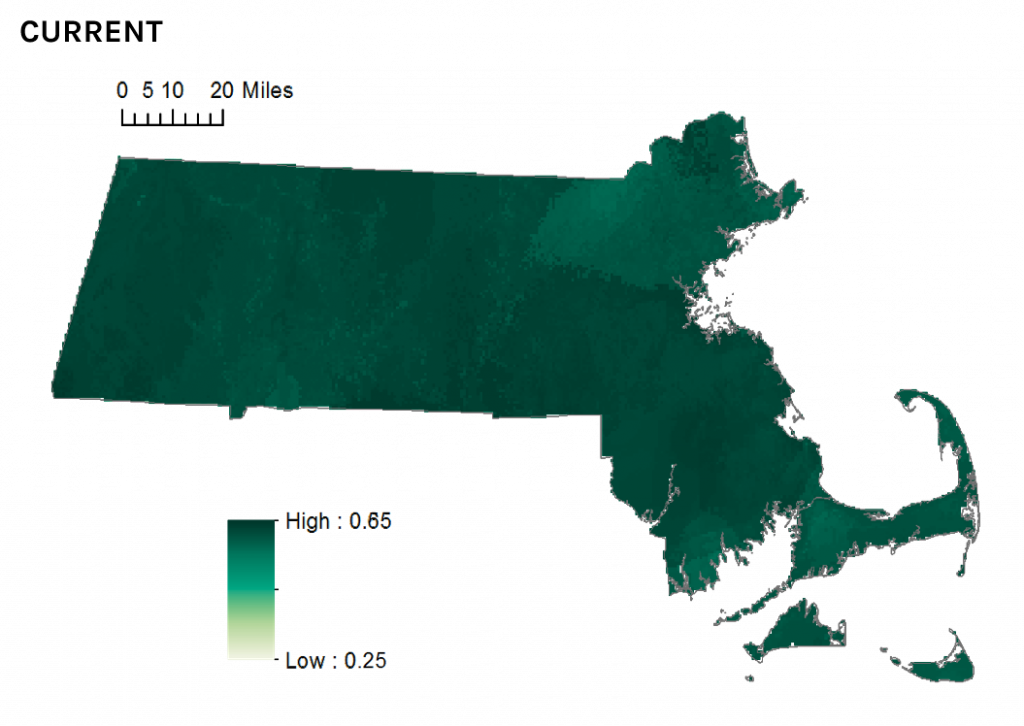

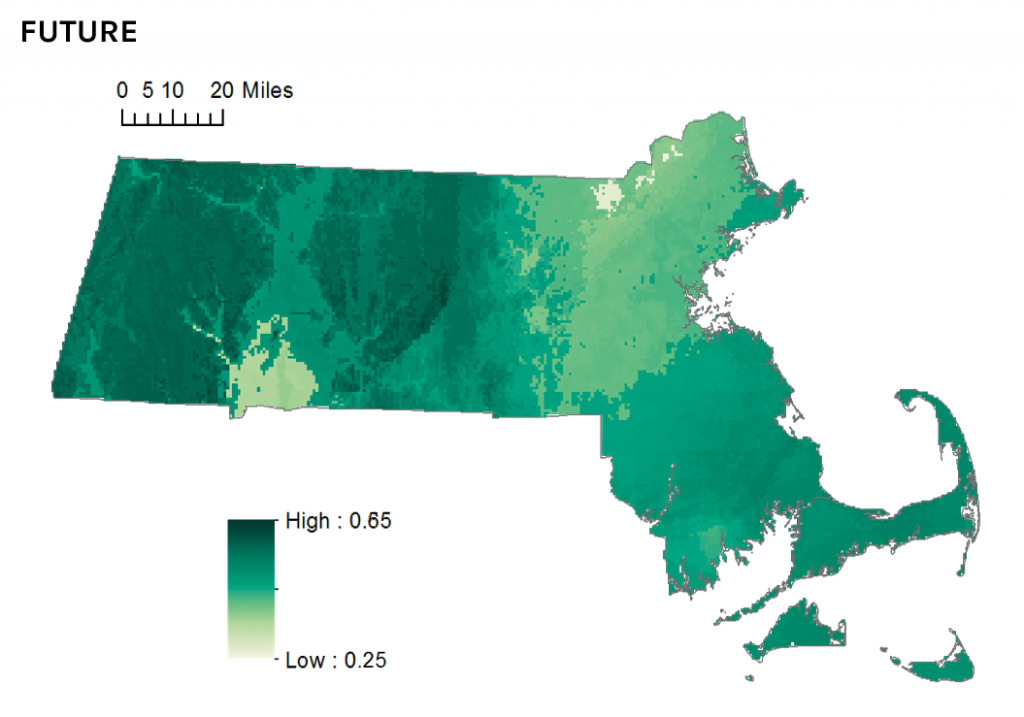

Current climate suitability for Ovenbird in Massachusetts.

Climate suitability for Ovenbird in Massachusetts in 2050.

How to read the climate suitability maps >

Keeping Large Forest Tracts Intact Will Lessen the Stress Ovenbirds May Face

Research has found that Ovenbirds require large intact expanses of forest habitat for successful breeding. This could be in part due to the fact that larger undisturbed forests have lower risk of nest predation and brood parasitism. Therefore, maintenance of large tracts of mature forest is crucial to future conservation of Ovenbirds in Massachusetts. Such areas will continue to be threatened by suburban development and associated habitat fragmentation.

Additionally, climate change may add to the stress of losing intact core habitat, because warmer temperatures may reduce the soil moisture levels that influence Ovenbird’s food resources (mainly insect larvae gathered on the ground).

Conservation Is Needed for the Full Life Cycle of a Migratory Bird

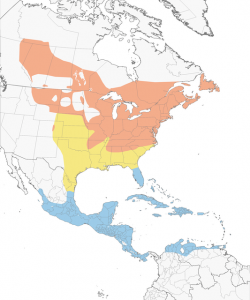

Distribution of Ovenbirds during breeding (orange), migration (yellow), and winter (blue) periods. © Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Neotropical Birds

Ovenbirds migrate through the southeastern U.S., wintering mainly in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America – including areas that were recently damaged by Hurricane Irma. Throughout its annual life cycle it is vulnerable to habitat loss and degradation, window collisions, and predation by cats.

Conservation of Ovenbirds demonstrates the broad suite of actions that are important for most

of our Neotropical migrant songbirds. Efforts to reduce losses throughout the full annual cycle are important. Action must be taken on their breeding, migrating, and wintering grounds to effect positive change in the population.

How Can We Help Ovenbirds and Others?

- Prevent forest fragmentation in the breeding range by supporting the efforts of local land trusts.

- Ensure that your backyard is a bird-friendly sanctuary safe from cats and potential collisions with windows.

- Support efforts to reduce window collisions at tall skyscrapers and other office buildings.

- Donate to organizations focused on protecting lowland forest habitats in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America—actions directed toward all those efforts will help reduce the pervasive impacts of changing temperature and precipitation patterns on breeding Ovenbirds in Massachusetts.

Ovenbirds are often observed strutting (never hopping) like a chicken along the forest floor. © Tom Benson