Tropical Storm Isaias arrived in Massachusetts on August 4, 2020, pushing heavy wind and rain through the Berkshires in the early evening before continuing northward. The storm also brought a slew of rare seabirds into the state, with sightings of at least 34 Sooty Terns, 2 Brown Boobies, a Franklin’s Gull, and a handful of other rarities on inland lakes as well as on the coast. This event was part of a rare but regular pattern of vagrant birds associated with hurricanes and tropical storms.

All hurricanes and strong tropical storms in Massachusetts have the potential to carry vagrant birds with them. Generally, the best sightings come in the wake of storms that spend time offshore over the Gulf Stream, before weakening or dissipating over southern New England.

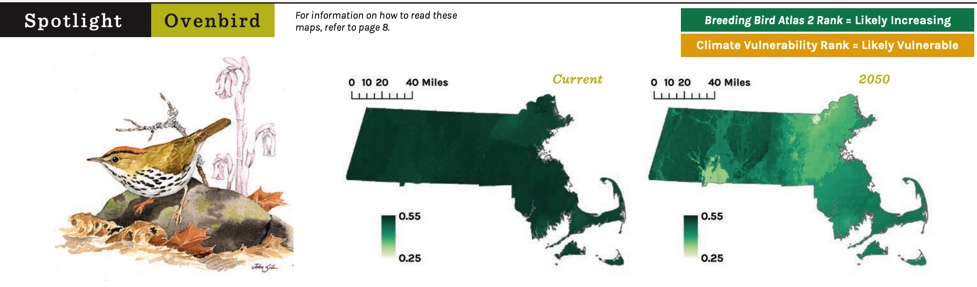

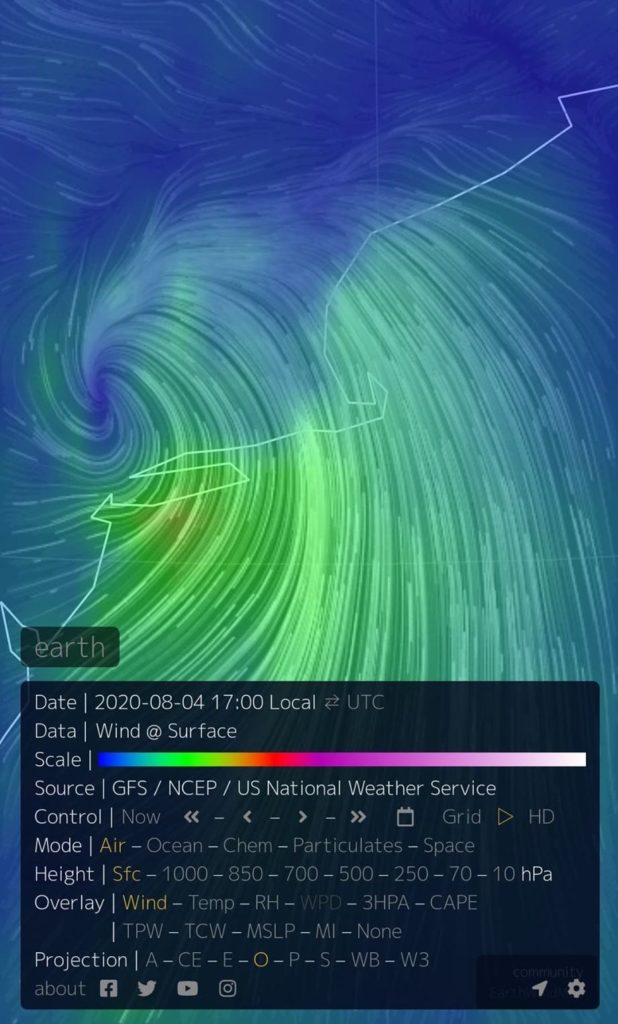

But storms that hug the coast from the southwest can also carry exciting birds. Most storms are big enough that even if their center sits over the New Jersey or New York coast, violent southerly winds sweep from the Gulf Stream into southern New England. This was certainly the case with Isaias, as seen in the wind speed graphic below.

From here, Isaias tacked directly inland through the Berkshires, making it a great candidate for delivering pelagic species to large inland lakes. Indeed, while there were some reports of strong pelagic birding from coastal sites like Gooseberry Neck in Westport, there were equally exciting reports from Wachusett Reservoir, Quabbin Reservoir, and even smaller lakes in the Berkshires. Sooty Terns, Phalaropes, Jaegers, and shorebirds dropped onto many large bodies of water throughout the state.

Stronger storms in the past have produced even more spectacular results. In 2011, Hurricane Irene brought an incredible variety of seabirds into Connecticut and Massachusetts. and resulted in at least one eBird checklist from Quabbin Reservoir that reported a Sooty Tern, an incredible White-tailed Tropicbird, a Leach’s Storm-Petrel, and more.

Often, storm-blown birds arrive at inland sites in bad shape. Many perish, and some return to their offshore or coastal habitats. Very few stick around for several days.

Remarkably, one Sooty Tern that appeared during Isaias has hung around on Wachusett Reservoir. The bird was reported feeding actively as of August 13th, more than a week after the storm, probably taking advantage of the reservoir’s abundant smelt. Smelt resemble Sooty Terns’ favored marine baitfish—mostly clupeiformes—in the subtropical Atlantic. This makes it the longest-lingering storm-driven Sooty Tern in Massachusetts, and quite possibly, in New England. It may leave any day now, and in fact, it’s likely to depart sooner rather than later. If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s worth looking for!