Pine Warbler © Andy Morffew

“The Pine Warbler is the gentle, modest minstrel of the pines…Its sweet monotonous song harmonizes well with the sighing of the summer wind through the branches, while shimmering heat-waves rise from the sandy soil.”—Edward Howe Forbush, 1929

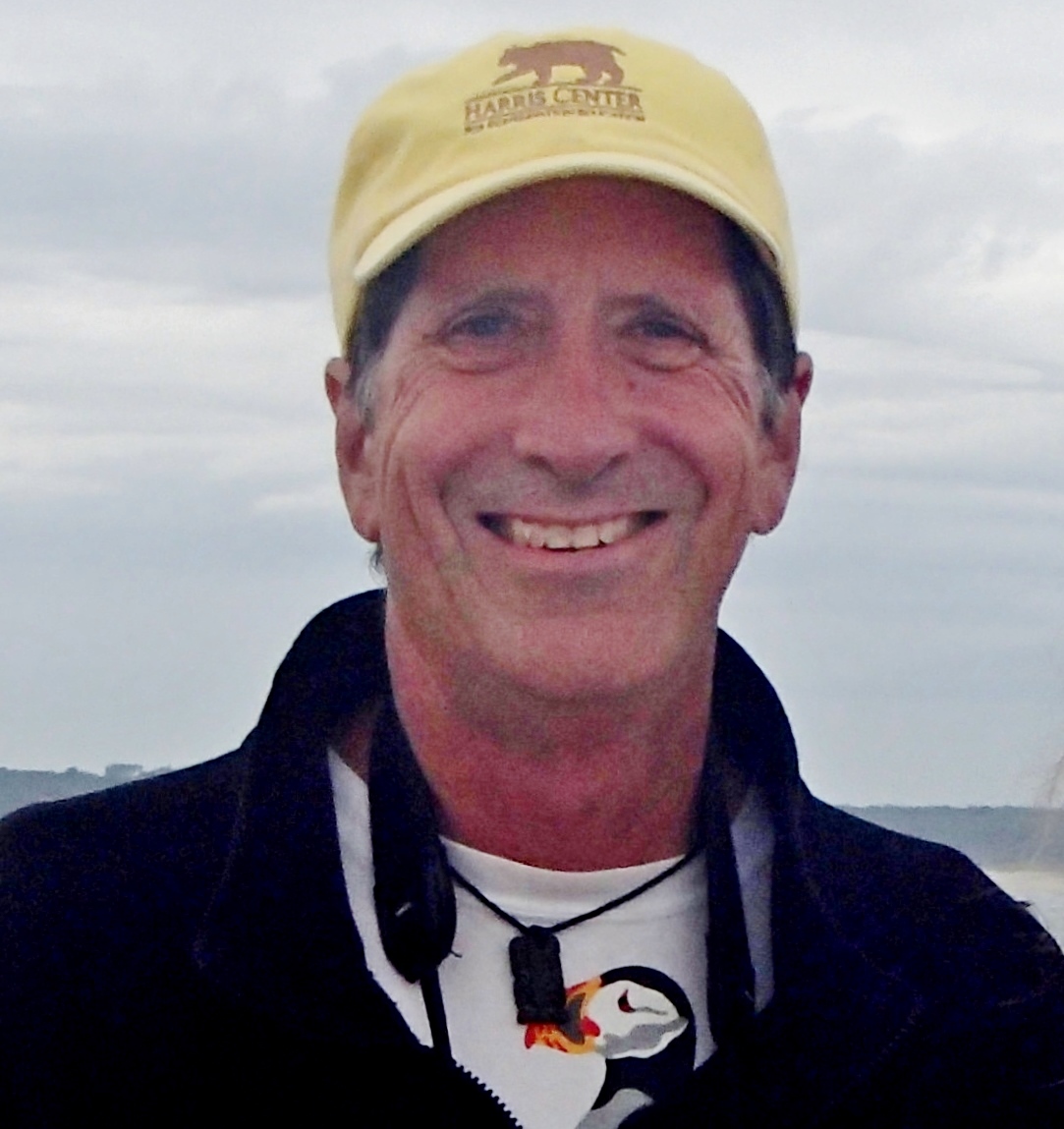

As its name suggests, the Pine Warbler typically shuns deciduous woods or high-altitude stands of spruce and fir. Rather, it goes where the pines are, and pre-Colombian Massachusetts certainly had plenty of pines. Tall White Pines, intermixed with resinous Red Pines, covered large portions of the state. Gnarled but venerable Pitch Pines dominated the sandy forests of Cape Cod and the Islands. Of course, after the arrival of colonists, homes and farms sprang up as the trees went down. Even as acres upon acres of pine forest disappeared across the state, Pine Warblers persisted for many years on Cape Cod.

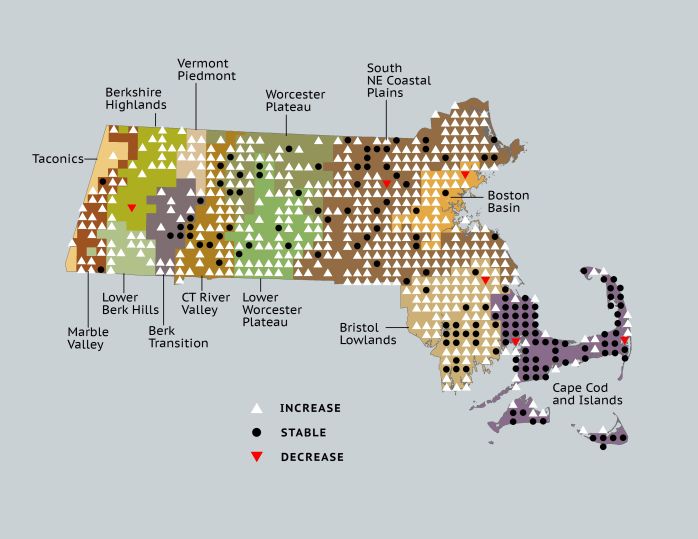

Trend in Massachusetts

The Pine Warbler has had extraordinary success in Massachusetts since our first Breeding Bird Atlas in the late 1970s. Pine Warblers persisted on the Cape and significantly increased in almost all of the rest of the state. The Breeding Bird Survey also indicates an increasing population of this short-distance migrant.

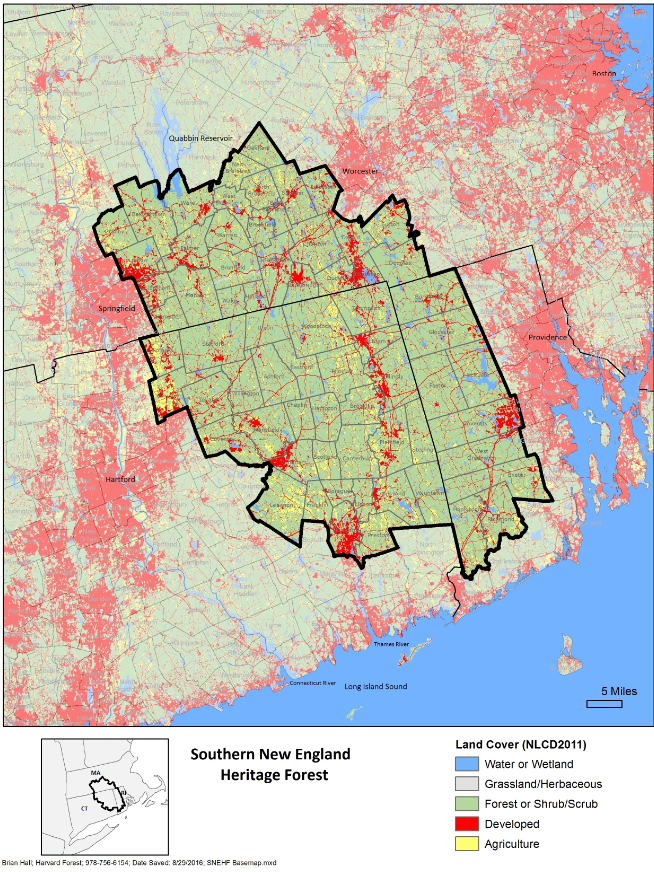

Pine Warbler change in presence between Breeding Bird Atlas 1 and Atlas 2.

Did You Know?

Pine Warblers are one of two warbler species that regularly stick around in Massachusetts in the winter. They can often be seen at suet feeders, so keep an eye out!

Attend our Birders Meeting on March 19 to learn more about warblers.

Please consider supporting our bird conservation work by making a donation today. Thank you!

In ornithology, as in most disciplines, there are inevitably “giants” whose profiles stand taller than those of their peers. Such a figure was Edward Howe Forbush, a prominent Massachusetts ornithologist living from 1858–1929.

In ornithology, as in most disciplines, there are inevitably “giants” whose profiles stand taller than those of their peers. Such a figure was Edward Howe Forbush, a prominent Massachusetts ornithologist living from 1858–1929.

Hi all,

Hi all,